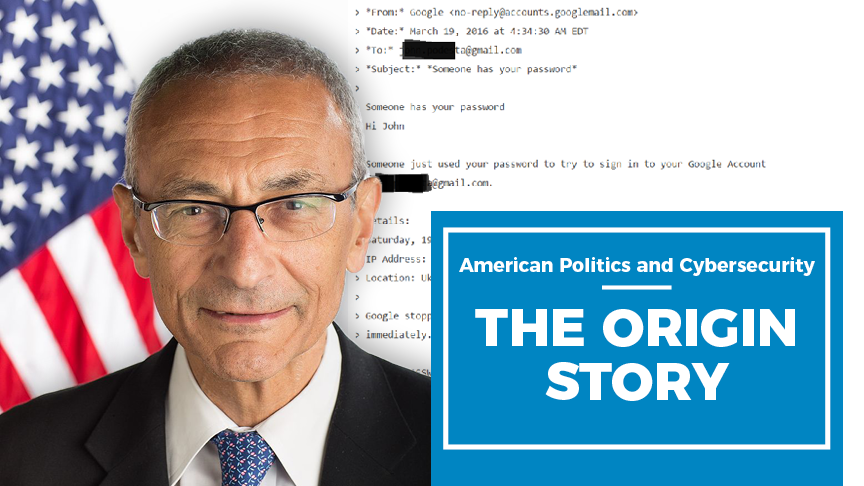

American Politics and Cybersecurity: The Origin Story

When Senator Kamala Harris announced her 2020 Presidential bid, she took aim at the current Administration, claiming that foreign powers are “infecting the White House like malware.” The comments were significant, not only for the Harris campaign, but also for cybersecurity. It signals a shift for cybersecurity from overlooked server rooms into mainstream lexicon, propelled by political rhetoric.

It’s not surprising that cybersecurity has found a home in politics. The 2016 Presidential election was scarred by digital manipulation, theft, and leaks. One of the most infamous political cyber incidents was the email hack of candidate Clinton’s Campaign Chairman, John Podesta.

Podesta was the victim of a spear phishing email, which is a targeted, personalized email attack that tricks victims into clicking a malicious link or taking an action that allows the attacker to steal information.

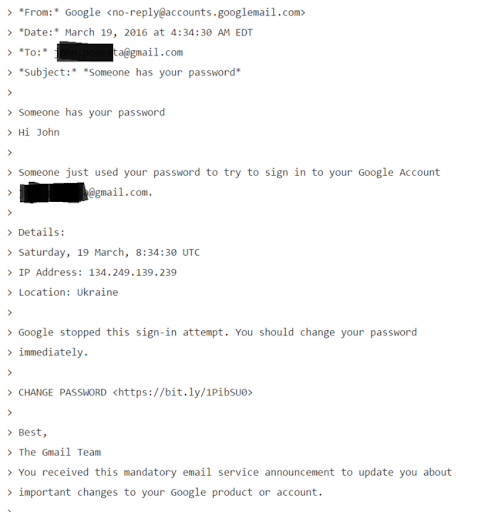

Podesta received the spear phishing email in March of 2016. The email, below, revealed a somewhat sophisticated social engineering attack that urged Podesta to change his password “immediately” because someone else used his credentials to log into his Gmail account. The attackers, later to be revealed as Fancy Bear, an infamous Russian-based hacking group, spoofed their identity and included a link for Podesta to reset his password. The link itself features a common strategy used by social engineers: a shortened URL, using the service Bitly. This helps attackers obscure a malicious link.

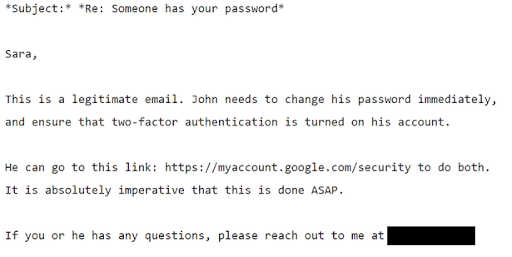

The story takes an interesting twist from here. Podesta himself did everything right. He did not click on the malicious link. He instead forwarded the email to his staff, who then sent it along to a security team. After investigation, the security team thought that the email was a legitimate alert, and urged Podesta to change his email address. To their credit, they passed along a safe credential change link and instructions, directing Podesta to the official Google homepage.

The fatal error was in the next, and final, line of communication. When Podesta’s staff sent back to him the security team’s recommendation, instead of directing him to an official Google site, they sent him the original email’s malicious link. Podesta clicked and then entered his credentials into a site under the Fancy Bear domain. Fancy Bear harvested his credentials, gained access to his personal gmail account which led to the release of hundreds of personal and work-related emails, and influenced an American presidential election.

It’s not unreasonable to be surprised that the Podesta team didn’t have a response plan for these types of social engineering attacks. As a prominent figure in a modern election, any forward thinking staff member may have recognized the potential for Podesta to be targeted. What was also curious was the multiple lines of communication that ultimately obscured the security team’s instructions to Podesta. When the stakes are high, the security team ought to have a direct line of communication to the asset they are protecting.

As the 2020 election accelerates, expect a renewed focus on cybersecurity. Candidates ought to make it a focal point, both in policy and practice.